Tour of The Sydney Opera House, Sydney, Australia

–

I think about alternate timelines a lot. About the infinite number of things that had to happen, of decisions that had to be made, for this reality to come about.

What if I had taken side streets instead of the freeway that one time I drove home in 2006? What if we had eaten Chinese food instead of Greek all those years ago? The potential ramifications of these tiny actions are why it takes me forever to answer simple questions like, “Paper or plastic?”, and why I spend way too long figuring out what I’m going to have for dinner.

Because it’s not just the big decisions that change the path of our lives. It’s a thousand little decisions, too.

Some days, I sit around and think about how things would be if I and others had chosen differently. As I contemplate these parallel universes, it makes my life feel absurdly fragile.

Consider my relationship with Rand. Contrary to appearances, I’m not a fatalist when it comes to romance. I don’t believe that he and I (or any two people, really) were meant to be. A million little things had to happen for us to meet. A million little decisions made by me and others that led us to the reality we’re now in.

If I trace it back far enough, I have to accept that the time I stood in the CD shop when I was 13, deciding between an album by Weezer or one by Counting Crows, had a lot to do with it. Which is somewhat terrifying.

Or maybe it isn’t. I mean, if Rand and I hadn’t met one another, we’d probably have been okay, right? I know that he’d have found someone to love him (unless being good looking and successful and twinkly-eyed is somehow unappealing in all those other universes). And I could have convinced some near-sighted fool to spend their waking hours with me. Maybe.

But I don’t quite know if I’d be nearly as happy in those realities as I am now. The idea of missing out on this life, on this marriage, on this husband … well, it’s all kind of depressing.

The flip side of that coin is this: when something goes terribly wrong, I think of all the different ways it could have been avoided. I wonder if the plane of existence that I find myself in is indeed the right one, or if there’s a better incarnation out there: where the people who were taken from us too soon still thrive, where fatal car accidents were merely fender benders, where ugly divorce proceedings were nothing more than spats.

This is a pointless exercise, and if there’s any lesson to be gleaned from it, it’s this: be thankful for what you have. If the outcome of something is even remotely good, if we can come even close to a happy-ish ending, then we’re lucky. There are so many other parallel universes in which things didn’t go right.

Why such a long preamble about destiny and fate and alternate realities? Because of the Sydney Opera House.

–

Its mere existence was so unlikely. So much was left up to fate, and a thousand different decisions had to be made for it to exist. The story twists and turns and the outcome of all of it seems, near the end, to be very, very wrong. But then the arc of the story curves once again, and the tale manages to end on a note that is rather happy-ish.

And that’s all we can really ask for.

This was not my first time visiting Sydney, or the Opera House. I was there once, years before, and even had the unique privilege of getting food poisoning from the one of the glamorous restaurants inside.

But it was my first tour of the Opera House. I was late for my 9:30am tour, and had to join one that began half an hour later. I’m pretty sure that had I made it on time, I’d be the Queen of Sweden by now. #alternatetimeline

The Opera House was built on Bennelong Point – a tapering finger of land that stretches out into the harbor. It had originally been sacred Aboriginal ground (called Tubowghule), but since we humans have a nasty habit of trampling on anything that’s sacred to someone else, it became a military fort, and later a tram depot (housing old trams that were no longer in use).

In the 1950s, someone realized that it was an ideal spot for the new opera house the city was planning. A design competition was launched to help select the new building, which was to have two separate performance halls. Hundreds of entries were submitted from all over the world.

One design came from a young and relatively unknown Danish architect named Jorn Utzon. On the day of the judging, his vision – of two buildings composed of a series of white, billowing sails – was put into the discard pile.

Yup. The discard pile.

And there it would have remained, and the path of history would have taken another course entirely, had it not been for Eero Saarinen. Saarinen was one of the judges for the competition, but arrived late, after many submissions had already been discarded. When he got there, he demanded to see the drawings that had already been dismissed.

Utzon’s caught his eye. He pulled it from the pile, pointed to it and said something dramatic along the lines of, “Gentleman, this is your opera house.”

Original estimates for the construction of the opera house were 3 years and $7 million dollars. They were waaay, way off.

The main problem was this: no one knew how to construct Utzon’s design. Nothing like it had ever been done before. Several years were spent augmenting the design (slightly) into something more feasible and trying to figure out the logistics of it. The final answer became known as “The Spherical Solution.” The sails would be, essentially, cut segments from a sphere. The segments could be cast on-site from concrete, and the exposed structure would be seen from the inside of the opera house (as Utzon had envisioned).

–

–

In 1963, the base of the building (on which the sails now rest) was completed. The project was now two years behind schedule. Work on the sails began soon after.

By the mid-60s, a new government was elected in New South Wales. The new Minister of Works – a man who reportedly had “no interest in art, architecture, or aesthetics” – began questioning a lot of Utzon’s work. The cost, the schedules, the design were all scrutinized, and payments to Utzon ceased. Utzon’s attempts to continue with the project were quashed. Every suggestion or request he made was denied. He could do nothing.

Under mounting pressure, he eventually resigned as chief architect, and left Sydney. He never returned to Australia. At the time, the sails were almost complete, and the total cost of the Opera House was around $22 million – 3 times the original budget.

–

–

–

A new group of local architects were put in charge of the building, and they completed the interior – putting in place a design that was radically different from Utzon’s and (forgive me for editorializing) kind of crappy. And they still managed to spend a fortune.

By 1973, 7 years after Utzon had left Australia, the Opera House was finally completed. It had taken 16 years, and cost over $100 million dollars.

Utzon was not invited to the opening ceremony. His name was nowhere to be seen in association with the building.

In some universe, the story ends, rather tragically, there. Fortunately, in the reality in which we live, the saga was not over.

The wounds took a long while to heal, but after enough time, it seems that they did. In the late 90s, the government of New South Wales and the Sydney Opera Trust began talks with Utzon, and he was eventually reinstated as architect for the building. He was asked to create a list of design principles that would serve as reference for all future changes planned to the building.

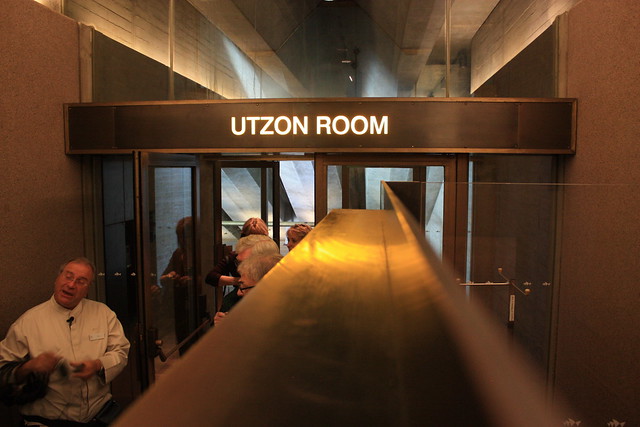

Remodeling began on the interior of the building in order to bring it into line with Utzon’s original vision. The first renovated room to be completed – aptly named the Utzon room – opened in 2004.

–

It is lovely. A giant tapestry – designed by the architect himself – lines one wall. The floors are made from a Danish wood, and need to be washed in a traditional manner that involves the use of white clay, and requires a four-hour drying time. They are washed down on the opening night of every performance, which happened to be when I was there.

–

–

The tour wound around the back of the building, which had a sweeping view of the harbor. Embracing this panaroma was part of what set Utzon’s submission apart from all the others: his design was the only one to place the two performance halls side-by-side, so that the harbor could be seen from both buildings. Everyone else placed one hall behind the other, thereby blocking the view.

–

–

–

Each year, scores of people come to the Opera House for tours, shows, and events. It generates enough revenue to cover nearly 85% of the building’s operating budget – an unheard of percentage for many performing arts venues.

Current estimates are that the building will be structurally sound for the next 350 years. For generations to come, Sydney will have its Opera House.

–

Utzon died in 2008 at the age of 90. Though he never saw the completed Opera House itself, he would live to see the building listed as a UNESCO World Heritage site, and he would be honored repeatedly for his work. Today his name is now, quite literally, on the building.

–

But my favorite part of the story is this: the architect now in charge of implementing Utzon’s vision for the future of the Opera House is his son, Jan.

There are countless other timelines for the Opera House – an infinite number of outcomes that could have been. In some universe, Utzon’s design was never chosen at all. In still another, it was built on time and on budget, and he roamed the halls of his finished masterpiece a contented man.

And maybe in still another, the building was made of gingerbread and was devoured by giant mutant ants which later terrorized the entire continent.

But in this reality, we have Utzon’s opus – shimmering white sails that emerge from the water. And we have an ending that is very close to being happy.

–

Given how many things could have gone wrong, I have trouble asking for more than that.

Leave a Comment