What’s It Like To Record Your Own Audiobook?

This is the face of a woman in over her head.

My agent was the first to tell me my memoir would be available in audiobook. At the time, I couldn’t imagine that too many people would consume my book by listening to it. It’s a book! It’s supposed to be read! On pages! Perhaps even paper ones. But audiobook books have steadily been making a rise, to be enjoyed not simply by those poor souls with a long commute, but by all of us poor souls, as we go for runs or sit on planes or do the dishes or try to drown out the nervous voice of self-doubt that constantly echos in our skulls (or is that just me?). My book was going to be recorded. People might even listen to it.

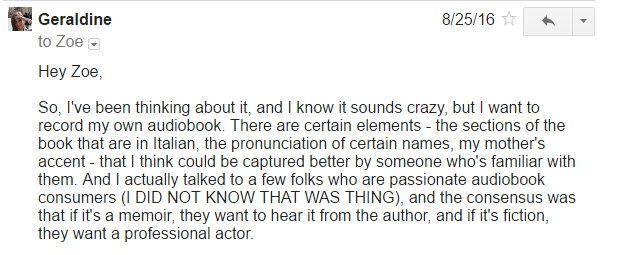

She explained that they would hire a voice actress to do it – a professional who was used to reading out loud. I made a rather miraculously quick leap from learning of the existence of my hypothetical audiobook to knowing, without any doubt, that I wanted to be the one to record it. I told Zoe as much. But it’s kind of a hard case to make.

The thing that I didn’t mention to Zoe is that while I think it’s true that people often want to listen to books as read by the author, it’s usually because those authors are famous people with awesome voices, like Negin Farsad or Phoebe Robinson.

But I asked Zoe to make the case to my publisher for me to read my book, instead of having a qualified professional do it.

Miraculously, Hachette agree. Then I learned what I had gotten myself into. The finished audiobook was an estimated 9 hours long, which means that I’d be in the studio recording for about 18-23 hours. All that time, I would be talking.

Have you ever tried talking for two straight hours? No pauses in conversation. No conversation at all! Just you and a microphone, and a book that you wrote.

My publisher set me up in a small studio recording studio locally – one operating inside someone’s house. So last week, I drove up to North Seattle and entered a stranger’s windowless, soundproof basement via their garage. (Did you hear that thud? That was my mother having a heart attack.)

The studio felt a little like a maze – little rooms all connected together, lined with sound-absorbing and sound-diffusing materials (the former stops sound from leaving the room. The latter stops it from echoing), each one packed with musical instruments – guitars, drums, even a grand piano – and recording equipment. My office for the next three and a half days was a little room in this jumble – perhaps 4’x4′ in size, paneled in sound absorbing foam. I sat opposite a microphone, reading off an iPad perched on a music stand in front of me.

Jeremy, the audiobook’s producer, was in another room, and while I couldn’t see him, I could hear him – and myself – through a pair of massive headphones. It was strange, because the audio equipment was so good, it sounded like Jeremy was in my ear. A couple of times I was tempted to pick my nose, but I’d somehow convinced myself that if he could hear me that clearly, he could also see me.

With a microphone that good, every sound is picked up. Like, everything. On our first day of recording, I had a kale salad for lunch, and for the rest of the afternoon, my stomach made gurgling noises which kept necessitating us doing another take (note: the farting did not commence until much later, after I left the studio. You’re welcome, Jeremy). If you move the slightest bit, the mic will catch it (sitting on a squeaky wooden chair, this meant I couldn’t even shift my weight). Even the sound of my hand brushing hair out of my face was too noisy.

During the down time, when weren’t recording, I would brush my hands against my jeans or wiggle my fingers and listen to the noise it made. I felt like I had a superpower. I could hear the passing of time.

It wasn’t until I started reading that realized I had no idea what I was doing. For the first chapter or two, I kept trying not to breathe because I thought it would ruin the recording – so I’d wait until the end of a paragraph, and by then I was gasping. It took me a while to master the whole breathing-as-I-went thing, which was kind of demoralizing, because you’d think that after 36 years breathing was something I would have down.

I managed to handle the breathing okay, but then realized a few other things about my book:

- There are four different languages across the various chapters. English, Italian, Spanish, and French. I speak these first three with various levels of competence. But my French is pitiful. And I had to speak entire sentences in French. While being recorded.

- My friends and family have a lot of non-American accents.

- There are words in my written vocabulary that do not exist in my spoken vocabulary. So I’ve never actually said them aloud. Jocundity. Apotheosis. Sybaritic.

- My pronunciation of “penchant” sounds really pretentious.

These were things that I had sort of anticipated. I knew that my mom’s accent was challenging, but I could do a reasonable facsimile of it. I knew that I’d have trouble pronouncing Hector Guimard’s name. I know that my voice is heavily inclined to vocal fry, and that my accent is kind of weird at times (I over-pronounced the “g” in words ending in “-ing”).

But then there were things I hadn’t even begun to imagine. My friend Ciaran, who is English but now lives in Australia, has speaking lines in the book. But I could not for the life of me make him sound like anything but a constipated Dame Edna. I found myself quietly cursing every self-indulgent instance of alliteration I’d used. And there was a lot of dialogue in the book, usually between me and Rand. This meant that I had to an impersonation of Rand, and then answer him in a voice that was close to my own (so you knew it was me talking) but still distinct from my voice as a narrator. I HAD TO DO NUMEROUS VOICES FOR MYSELF.

And I realized that I had inadvertently memorized huge swaths of the book while writing and editing it. This became a problem, because the final round of proofreading meant that some of these sentences had changed and I could not for the life of me read them as they were now written.

But despite all of this, once I got going, things chugged along okay. I could get through a few paragraphs or even a page with just a few mistakes. I think that Jeremy was actually somewhat surprised that I started to get the hang of it, considering I couldn’t even breathe properly at the start. I’d hear him in my ear over the headphones saying things like, “One more time on that last sentence.” or “Let’s take that from the top of the paragraph.” He’d let me know when I moved too much or when my stomach made a weird sound (“Just a little bit of noise on that last sentence,” he’d say, diplomatically.)

The problem with a task like this one is that once you start messing up, it’s very easy to psych yourself out and mess up even more. Miraculously, though, I never got too caught up and frazzled by my own thoughts. The problem more often than not was physical, and not mental (a first for me!) By the end of the afternoon, my mouth would become dry and you’d hear pops from tiny bubbles on my tongue and teeth (it sounded like I was eating Pop Rocks). Green apples supposedly help “lubricate your throat” (ew), but after a while not even that could alleviate the crackles.

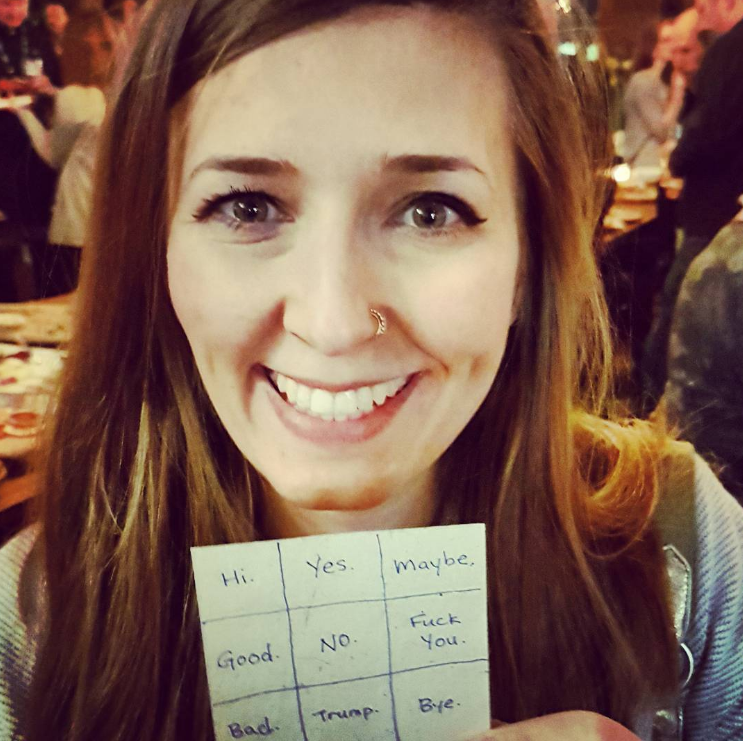

One day, in the early afternoon, my voice was just gone. It didn’t hurt, but there was simply nothing left in the tank. In the evenings, I avoided talking to save whatever voice I had left. I made this little chart of responses for a party I went to, and would point to an answer.

And then, as with almost everything else that pertains to this book, by the end, I’d finally figured out how to do it. We finished a day early. By the time I recorded the book’s intro and outtro (essentially the credits), I did it in one take, and Jeremy seemed shocked.

Is recording your own audiobook easy? No. Being literate is a prerequisite, but not the only skill you need. And while it was definitely challenging, it wasn’t grueling. It was even kind of fun (for me, at least. Jeremy’s opinion may differ). And next time – because I’m determined that there will be a next time – it’ll be even easier.

—————

Tips for recording your own audiobook:

- Wear quiet clothing – stuff that doesn’t rustle. Don’t wear any noisy jewelry.

- Use an iPad. The rustling of pages as you turn them is too noisy.

- Don’t rush! Jeremy told me the biggest novice mistake is trying to go too quickly. The actual pace of reading out loud is slower than is comfortable. Like a children’s story hour.

- Breathe. For the love of god, breathe.

- Read the book beforehand – heck, try reading it out loud beforehand (I did, during the editing process, to make sure sentences flowed right).

- Look up the pronunciation of words/names you are unsure of.

- Eat green apples – they help lubricate (ew, sorry) your throat.

- Stay hydrated. I drank a lot of Throat Coat (ew, sorry again) tea with honey, which helped, though Jeremy warned me that liquids that are too hot can actually dry your throat out.

- Be careful what you eat! Stomach noises can get picked up on the microphone. I stuck to soups after my kale salad debacle, and kept a pillow on my stomach to muffle any sounds.

- Just keep trucking along. When I made mistake, I’d immediately reread the sentence, without pausing to beat myself up. If I focused too much on the mistakes, I’d lose momentum.

- Know your limitations: if you suck at accents, consider not doing them. If you want to show off your acting chops, go for it (but don’t go overboard – listeners will get exhausted if it’s a non-stop theatrical performance.)

- Relax. It’s your story. You are uniquely qualified to tell it. (Note: this may not actually be true, but I kept telling myself this until I believed it.)

- Have fun.