The Mutter Museum, Philadelphia

A simulation of an arm amputation at the Mutter Museum.

–

I have a persistent and haunting memory from my childhood.

I must have been 8 or 9 years old, and I was at the county fair in Florida. County fairs in the south are a big deal: they’re fun but also sort of creepy and disturbing. The structures are temporary, there’s extension cords everywhere, and you feel like the entire place could go up in flames or collapse. I wonder if that’s part of the appeal – that you might die at any moment.

So you eat lots of funnel cake and try to live in the now.

On this particular outing, I’d spotted a sign for the side show; I was captivated by airbrushed paintings on the side of one long trailer. There was a man who weighed 600 pounds, but his likeness on the side of the giant metal container suggested not that he was overweight, but rather that he was just huge, in a Paul Bunyan kind of way.

There was another painting of a petite woman who was nicknamed “The Living Doll.” That sold me on the entire affair. I insisted that we go in. My mother flat-out refused, and stared warily as another adult in our group acquiesced to my demands, and escorted me in.

Needless to say, it was not as advertised.

The stage was a poorly lit, poorly maintained trailer. Neon lights buzzed overheard, and our footfalls made the entire place rattle. The Paul-Bunyan-type giant turned out to be a tired-looking obese man. He sat in a giant recliner, watching a small television and paying little attention to the few people that wandered through. The Living Doll was a woman with Achondroplasia with a tidy afro haircut. She sat in her small section of the trailer doing absolutely nothing, looking bored and rather unhappy.

These were just regular people, sitting in a trailer, trying to make a buck. That realization hit me, even at my tender age, and I was awash in a strange mix of disappointment (in the show itself), and shame (that I’d reduced my fellow humans to the level of a spectacle).

Maybe that’s why the memory stuck with me for so long: because I learned something important, and it happened naturally and organically. There was no heavy-handed soliloquy from an adult. There wasn’t some some sort of platitude, hammered into my head through repetition. I just realized it on my own: gawking at people is a really shitty thing to do. Even if you’ve paid admission to do it, you don’t actually have that right.

That feeling hit me again when I visited the Mutter Museum in Philadelphia.

–

I’d wanted to go there since I was a kid, after seeing the museum director as a guest on David Letterman. I remember writing down the name of the museum on a scrap sheet of paper. Years later, it was one of the first internet searches I ever made – at the time, it returned very little information.

So you can imagine my excitement when I realized that the Mutter was in Philadelphia. My enthusiasm was leftover from childhood and so I didn’t question it. I didn’t stop to think that maybe, maybe, this wasn’t the sort of thing that I’d want to see as an adult. That maybe the lessons I’d learned would be in direct conflict to the mindset required to enjoy the museum.

I was going to go, no matter what.

The garden adjacent to the museum.

–

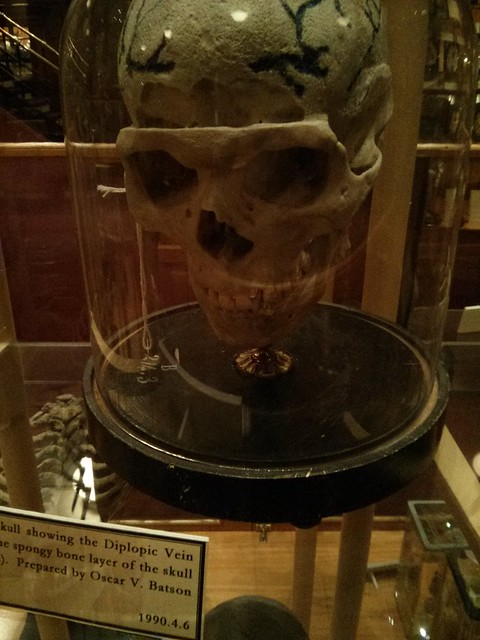

There’s no photography allowed inside, and I think that really is for the best, because there are actual human remains on display. It seems odd to be photographing them.

And so, I tell you with no small measure of hypocrisy that I did sneak in a few photos. I did my best to avoid taking pictures of anything too graphic (not sure how successful I was, as I shot from waist-level with my camera phone), but I did want to give you an idea of the museum’s collection.

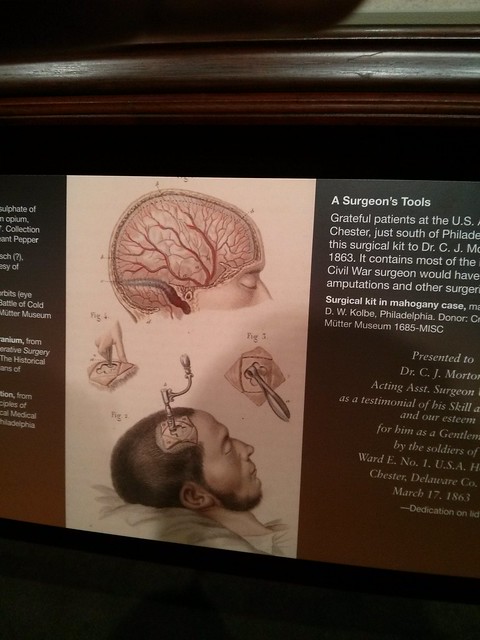

Not taking graphic photos was difficult because, well, the collection is graphic. I mean, it’s supposed to be. The collections’ original purpose was as a teaching and research tool for medical professionals and students. Much of it was amassed by Dr. Thomas Mutter in the 1800s, and to this day the museum remains part of The College of Physicians of Philadelphia.

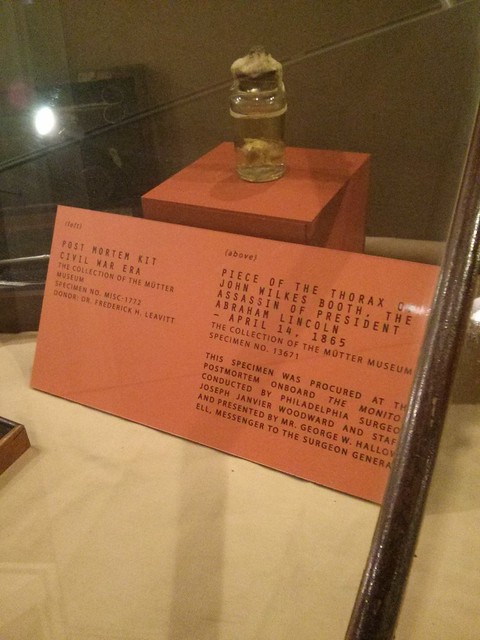

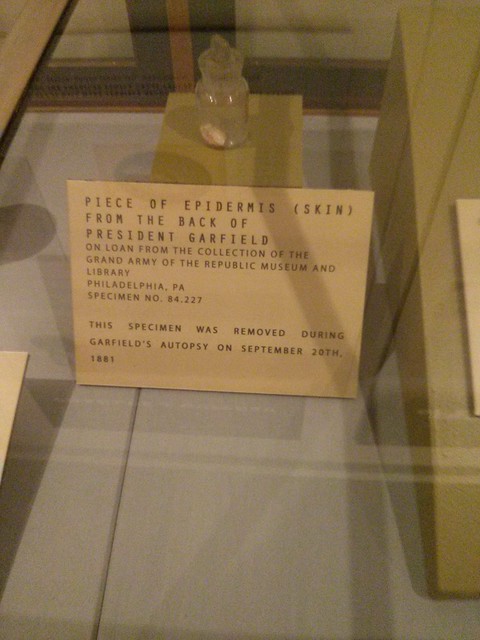

If the notion of looking at a collection of medical abnormalities and teaching tools from the 1800s sounds a bit creepy or off-putting, it should. The museum, to its credit, starts things off slowly. You enter through the gift shop, and the first exhibit focuses on an analysis of the assassinations of Lincoln and Garfield. It’s all rather clinical and fascinating; there are a few drawings and diagrams, as well as a couple of medical samples on display. The latter were tiny and jarred, so it was hard to tell what exactly they were:

–

I mean, how bothered can you be about seeing a part of John Wilkes Booth’s thorax? Especially when you don’t know exactly what constitutes a thorax?

There was a piece of skin from President Garfield, as well. If you are not particularly familiar with him (indeed, I was not), then reading about the details of his death will be more than a little disturbing. At the time of his assassination, physicians weren’t up to speed on antiseptic practices. There wasn’t a lot of hand washing going on. This is already bad form to begin with, but it becomes exponentially worse when you consider that the general practice when someone was shot was to remove the bullet. But first, they would probe the wound.

With their fingers.

–

Garfield contracted an infection from his “treatment” and spent his last few weeks in agony before his death. Many historians and medical experts believe he would have survived the shooting had proper sterilization techniques been used.

Now while all of this was morbidly fascinating, it didn’t feel particularly wrong. I suppose it’s because the remains that I’d seen (such as they were) and the stories told were of major political figures. These were people who were in the public eye, so I didn’t feel as though I was violating their privacy by reading the intimate details of their last few days.

But that wasn’t the case with the rest of the collection. I rounded the corner and I may have drawn in a sharp breath. The museum is small but packed. You enter on the second floor, but can easily see down a wide staircase to the lower level. Every wall is lined in high, polished wood cabinets. And inside is every sort of human remain you can imagine.

It is incredibly hard to stomach. And yes, there were stomachs.

View from the lower floor. If you look at the upper right corner of the picture, you’ll see a massive collection of skulls.

–

The Hyrtl Skull Collection, which you can partially see in the photo above, is one of the museum’s most popular features. It consists of 139 skulls collected by Josef Hyrtl, a professor of anatomy and renowned phrenologist. He collected the skulls throughout Europe (even after a bit of research, I couldn’t find out exactly how he obtained them. I’ve decided that perhaps I don’t really want to know). His goal was to find commonalities in the structure of the skulls of similar ethnic groups. To this day, they remain grouped geographically – the Italian skulls here, the Spanish ones there. Hyrtl wrote notes about the lives of those skulls, of the people to whom they belonged, directly on the side of them.

Some are regular people. Tradesmen, sailors, shopkeepers. Others feel like characters out of a novel by Dickens or Tolstoy. There’s a famous Viennese prostitute (who died quite young, if I recall, making me wonder how she became so famous in such little time), a tightrope walker, an eastern European herdsman who attempted suicide. There was one skull, badly misshapen, and the description under the name was simply “Imbecile”.

On the lower floor were the fetuses. They’d been preserved in various states. Some were dried and splayed out, a horrific reenactment of a dissection we did in 8th grade science class. Others floated in jars, surrounded by murky liquid, as they had for more than a century. Some were missing portions of their skulls, had malformations to their brains and other vital organs. Several were conjoined, sharing so many organs and systems it was impossible to tell where one stopped and a sibling began.

Several were just bones. A skeleton here, a skull there. This seemed less personal, somehow, and easier to look at.

–

Many of them never took a breath. A few that managed to be born died within a few hours. Some lasted a few days, and one or two managed to eke out several weeks of life.

Elsewhere, there were amputations. A jar of toes on one shelf, a dried-out foot on another. A thumb here, a face (dear god, an actual face) there. If you gathered all the pieces together you’d be able to compose several patchwork people, with a few parts leftover.

Relax! The foot in the jar in a wax model. But there were actual feet in jars elsewhere.

–

I was, on a personal note, rather transfixed by the brains. As I walked through, I kept reaching up to touch my own dented skull.

Incidentally, this is almost precisely where my own burrhole is.

–

Mine is now marked, and if it sat on the shelf at the museum, everyone would know its story. And yet I meet people on a daily basis who have no inkling of what happened that summer.

That’s the thing that may be so disturbing about the Mutter Museum: our bones reveal the secrets that we, in life, keep so well hidden. I don’t need to tell you about my brain surgery if I don’t wish to. I can hide how many cavities I had as a child, whether or not I had my wisdom teeth removed, how much time I do or don’t spend on my feet. Mind you, I have no problem divulging any of this – but it’s my decision to do so. The owners of all those disparate parts behind the glass don’t have that luxury.

–

Their secrets, their deepest parts, are laid bare for all to see. There’s nothing they can do about that. Did they willingly sign away their bodies before they died? Did the parents of those infants in the jars just give them up? Or did they live in a world where objections of that kind couldn’t be made by normal people?

And that’s what each of them were. Normal, average people, like the ones I’d seen in that trailer all those years ago. Some were afflicted by unusual illnesses, some were shaped slightly differently than most of us. Some suffered, some didn’t.

That could be said of any of us, couldn’t it?

–

I walked out onto a chilly, sunny day in Philadelphia, my mind agitated by everything that I had seen.

There’s no doubt that the museum has historical value – the path of modern medicine walks through the Mutter. The contents therein, as disturbing as they may be, are part of our collective history.

But there are nevertheless people involved. With feelings, and lives, and names. And I couldn’t help but think that gawking at their remains was a shitty thing to do … even if I had paid admission to do it.

Leave a Comment