Eastern State Penitentiary, Philadelphia

I’m starting to realize I visit a lot of old prisons. Well, maybe not a lot, but certainly more than the average person. Enough to where I can roam around one and find myself thinking something like, “This old prison reminds me of that other old prison!”

Can I tell you something? When you realize you’ve visited so many prisons that you can compare one to the other, it becomes sort of disconcerting. And you start to wonder why you can’t have a normal, healthy hobby, like tennis or mahjong or whatever it is that functional, healthy people spend their time doing.

But then you realize that tennis has always sort of confused you (30-love? What does that even mean?), and you don’t know anything about mahjong except that it sort of looks like complicated dominoes. So you go back to roaming cities and wandering around old prisons and it’s all rather creepy and exciting in precisely the same way that tennis isn’t.

So when, during our week visit to Philadelphia, I was told about Eastern State Penitentiary, an old prison turned museum, there was no doubt of how I would be spending at least one day of my trip.

Unfortunately, the day happened to be rainy and grey, but I suppose that doesn’t really matter in prison.

–

Eastern State Penitentiary (or, to use a delightfully creepy acronym, ESP), was built in the early part of the 19th century, after several decades of discussion and planning. It was, like many prisons built at that time, supposed to be revolutionary (as was Kilmainham, in Dublin) – a response to the jails that preceded it.

Prior to that time, jails were merely enormous rooms into which all manner of criminals – everyone from petty thieves to murderers – were held together. Even children would be locked up (either for crimes they committed, because everyone was tried as an adult, or because they had no other place to go when their own parents were imprisoned). It was incarceration for the whole family! Inside, it was a state of pure chaos (there were no mental institutions at this time, either, so often the insane were tossed in there, too, because why not?).

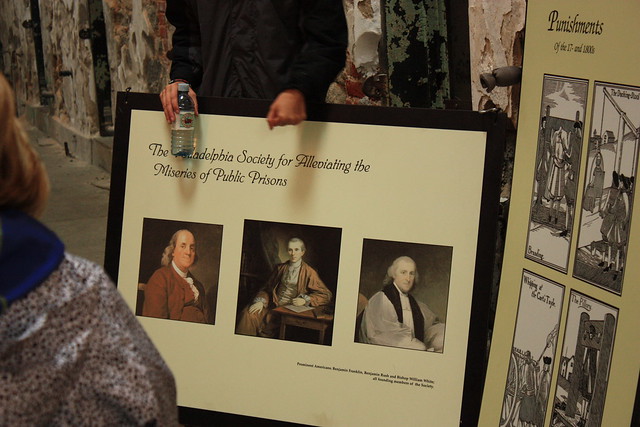

In the late 1700s, a group of prominent Philadelphians, including Benjamin Franklin and Dr. Benjamin Rush, decided to do something about the jail system in their state. They established The Philadelphia Society for Alleviating the Miseries of Public Prison.

The group was dedicated to finding the best wedding cakes in the region.

NO! I’m just kidding! The group was dedicated to alleviating the miseries of public prisons. I was just making sure you were still paying attention.

“It’ll be the bestest club, ever. And NO GIRLS allowed.”

–

They decided to create a new prison, the design of which would help foster regret and penitence in the incarcerated, thus rehabilitating them. This would be done not through corporeal punishment or abuse (which was the di riguer form of rehabilitation), but through isolation and physical labor.

From the ESP website:

The early system was strict. To prevent distraction, knowledge of the building, and even mild interaction with guards, inmates were hooded whenever they were outside their cells. But the proponents of the system believed strongly that the criminals, exposed, in silence, to thoughts of their behavior and the ugliness of their crimes, would become genuinely penitent. Thus the new word, penitentiary.

Each inmate had his own cell, and at the back of the cell opened up to a small, private courtyard where they could get exercise and fresh air. Keep in mind, though, the courtyards had high walls, and were quite small. They were only allowed one hour out of their cell each day, and pains were taken so that they weren’t out at the same time as their neighbors, ensuring their continued isolation. To further increase their isolation, hoods would be placed over their heads any time they might be in contact with other humans – even guards.

For the rest of the time, inmates were locked inside their small rooms.

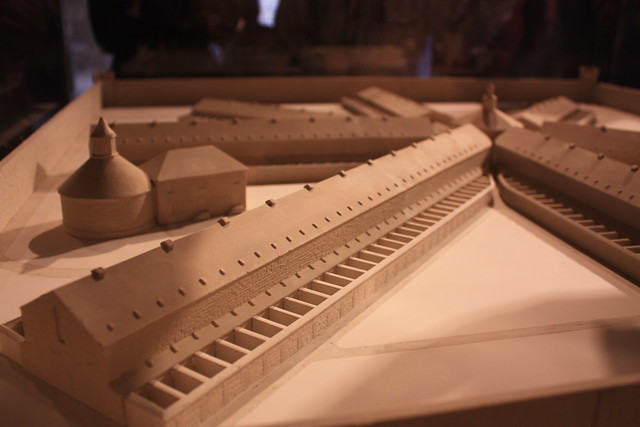

This model shows a cell block at ESP. Notice the small, high-walled courtyards on the outside of each of the cells.

–

The wreckage of a courtyard, behind one of the cells.

And while that seems a bit rough, keep in mind that prisoners as ESP were treated far, far better than those in other parts of the country or the world. Eastern State served prisoners hot meals every day, and each cell had a skylight, its own toilet, and heating. That’s right: it was one of the first buildings ever to have running water and a heating system – luxuries that not even the president enjoyed at that time.

The outside of the building was nevertheless designed to look intimidating to those who entered – like a sort of medieval castle. And sure enough, when my friend Nora (who graciously gave me a ride) dropped me off out front, I may have mumbled “Dear god” under my breath.

I mean, the place has friggin turrets:

Note: the gargoyles are NOT authentic; they are merely Halloween decor for the haunted house that takes place at the ESP this time of year. But they still freaked me out.

–

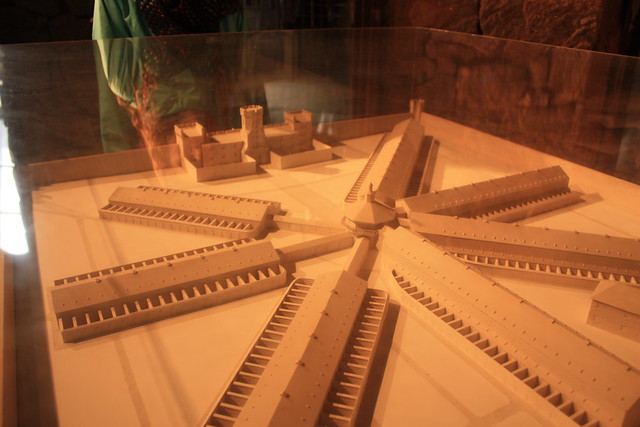

The original design of the prison was seven cell-blocks radiating from a central axis point, like spokes of a wheel.

–

From this central location, a guard could easily look down each of the cellblocks and see all the doors to each of the cells (once again, I was reminded of Kilmainham, and the panopticon style of the cellblocks there).

–

At least, that was the architect’s intent. Almost immediately, though, the original design was compromised. By the time the third cellblock was completed, the prison was already overcapacity. Many of the subsequent cellblocks were built with a second story up top, which meant that a guard could no longer easily look down and see all the cells.

Looking down one of the two-story cell-blocks.

–

–

The interior of ESP designed to look a little like a monastery. High, vaulted ceilings, white-washed walls, skylights and high windows.

–

–

–

It was thought that this would help foster rehabilitation – the inmates had nothing but “light from heaven” shining down on them.

The ESP gained worldwide attention. At the time, it was one of the most expensive buildings ever built, and prisons everywhere were modeled after it. Tourists came from all around – even as far as Europe – to tour the facility (remember, it was the 1800s, so traveling, like, three blocks would take you a month or something). With the increased attention came criticism. Many declared that the solitary confinement imposed on the prisoners was unhealthy, and that isolation would leave them ill-prepared to reenter society when the time came.

It seemed that ESP was not living up to the high expectations placed upon it.

Door to one of the cells at Eastern State Penitentiary.

–

Even the prison’s technological advancements proved to be lacking. The heating system was fueled by coal, and many of the inmates became ill with exposure to carbon monoxide. The plumbing system was constantly backing up. Disease spread easily through the facility.

By the late 19th century, it became clear that the ESP’s model of isolation and redemption was a failure. Apparently isolating someone from society does not, in fact, make them a functional member of society. Go figure.

Over the years, the solitary confinement approach was whittled away before it was abandoned entirely. More cellblocks were added, placed in between existing blocks. Cells now held two or three inmates, and the exterior courtyards were eventually demolished. A mess hall was built, as well as several exercise fields and recreational facilities.

The prison continued to be overcrowded, and upkeep for the enormous facility became incredibly difficult. Eventually, in the early 1970s, Eastern State Penitentiary closed. The city purchased the site in the 1980s, and there were plans for developing it. The ideas were strange and somewhat inappropriate – there was talk of putting in a shopping center, or apartment buildings, within the prison walls. The public successfully petitioned the government to stop the development and turn the location into a museum.

Which is a shame, because what this place really needs is an Orange Julius.

–

I took the guided tour, which walked through all of the facility’s history. It took us slightly over an hour, and we were able to explore several cellblocks that were otherwise closed to the public. Still, it wasn’t entirely comprehensive (not because the tour guide wasn’t wonderful, but because there’s a LOT of history to cover), and I didn’t have time to take all the photos I would have liked. So after the tour group dispersed, and I began to wander around the old prison on my own.

Which, I suspect, is how many horror movies begin.

And indeed, it was kind of creepy. I found a sign telling me that “The Klondike” – where prisoners in the early 20th century were sent for solitary confinement – was just down a set of stairs. I followed them, the ceiling so low that I barely could fit underneath it, and found a little alcove under one of the cell blocks.

–

It did not look like a nice place. It was more a crawl space than anything else. It led to a row of small, windowless cells.

Prisoners would be confined down here – alone – for up to two weeks. There was no natural or artificial light (the lamps are for the benefit of museum guests, and a new addition), no human contact, and very little food or water. The practice was abandoned in the 1950s.

Thoroughly creeped out, I headed back above ground. I took a few photos of some of the prison yards, and then darted inside a doorway when the rain began to fall too heavily.

A sign on the wall informed me that I had stepped into cellblock 15, which had been the final addition to the facility. This was where death row inmates were held.

–

“Oh, hell no,” I whispered, but nevertheless took a tentative step inside.

There was a panel on the wall with buttons corresponding to each of the cells – this cellblock had been the only one with electric doors.

–

–

Sufficiently spooked by my surroundings, I wandered back outside, and found that there wasn’t a soul to be seen anywhere.

Yeah, pretty sure this is DEFINITELY how horror movies start.

–

I decided perhaps it was time to return to a more populated part of the prison. I wandered back to the center hub, where all the cellblock spokes met.

–

Things here were marginally less creepy. Marginally.

–

–

In the 1920s, Al Capone was briefly incarcerated at the prison, and his accommodations illustrated how greatly times had changed. No longer were prisoners forced to sit alone with no contact from the outside world. Capone was able to outfit his cell with furniture and paintings; there was even a radio.

A re-creation of Capone’s cell at ESP.

–

The prison is in a state of “sustained ruin”. They aren’t actively restoring it, but they are taking pains to make sure it doesn’t fall to the ground. The result is wonderful: ugly and beautiful all at once.

–

–

Thanks a lot, Obamacare!

–

I loved the Eastern State Penitentiary – all in all, I spent nearly two hours there, between the guided tour and exploring by myself. I thought it was wonderful, but I understand that it’s not everyone’s idea of fun.

I happen to like wandering around old prisons by myself, slipping into cellblocks that are almost certainly haunted. And that’s probably a good thing, too, because I’m pretty sure that I’d suck at tennis.

—————

The Essentials on Eastern State Penitentiary:

- Verdict: Yes. If you have time, this is a great way to spend a morning. Much of the ESP is covered, so even on a grey day, you can walk around (it does get quite chilly, though, so be sure to bundle up).

– - How to Get There: I got a ride there (thanks again, Nora!), but took a city bus back into town. It’s close to several bus lines, and it’s a designated stop for both the Big Bus and The Philadelphia Trolly Works.

– - Ideal for: history nerds, true-crime fans, and anyone who likes off-beat, spooky stuff. I think this place would be a blast for teenagers, and also for people who suck at tennis.

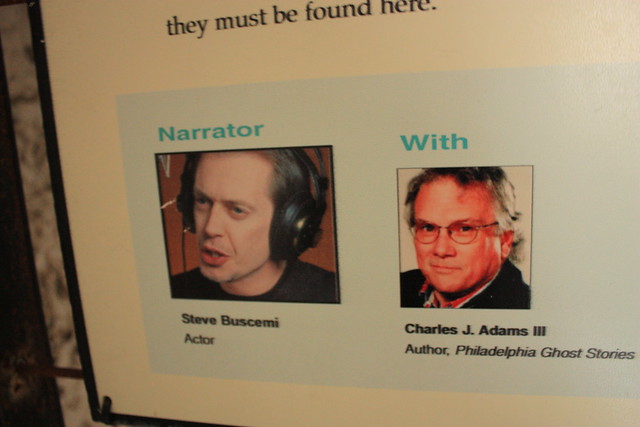

– - Insider tips: wear comfy shoes (there’s lots of walking to be done), and be sure to pee before you arrive (the only facilities are port-o-potties). Admission will either get you a guided tour or an audio tour. I did the former, which wasn’t quite as comprehensive as I would have liked, but still wonderful. I’ve heard that the audio tour is wonderful as well, and look who it is narrated by:

That’s right: Steve frickin’ Buscemi. Which is the bestest thing I have ever heard of, ever.

– - Nearby food: There’s nothing inside the facility, but there are a few cafes and restaurants within a short walking distance. I went to Fare, which was delicious, but perhaps a bit too frou-frou if you just want a quick bite.

– - Good for kids: The museum is not recommended for children under 7, and the audio tour is recommended for ages 12 and up. There are some special exhibits and tours for children, but I think that this place would be best appreciated by anyone in middle school or older.

Leave a Comment