Stratford-upon-Avon: Visiting Shakespeare’s Birthplace and Grave

I nearly forgot to tell you about the pilgrimage we made last summer to Stratford-upon-Avon: the home of that great Bard, of the man who wrote the sonnets and plays that shaped my awkward adolescence and escorted me to an awkward adulthood.

I will confess: at first I found the little town kitschy. The endless shops hocking knick knacks adorned with Shakespeare’s face, the touristy promenades, the people dressed in costume, reciting lines from famous plays. We rolled our eyes and questioned whether or not we should have stayed in Buxton.

I can’t quite say when that left me. It might be that Stratford wore me down with its almost desperate display of charm. It might be that I was finally able to see through any perceived affectation to the earnestness of it. That people don’t apply for jobs where they have to recite lines from Shakespeare unless it’s something they’re passionate about.

Or that if a town is going to be touristy about something, plays and literature are probably the most wonderful option there is.

Perhaps it was that after a few days, I started to see similarities between Stratford and my own beloved Ashland. And I realized that my favorite place in the world couldn’t exist without those same things that Stratford itself was built upon. That these were towns constructed by prose and sonnets. Their foundations rested on poetry; every building was reinforced with words.

Never let anyone tell you that art cannot sustain us.

There were statues of him, of course, in town. But he was architect of all of this. What was more surprising was to see monuments of a brooding Hamlet, of a mad Ophelia, of a young Prince Hal. His own creations carry almost as much weight as he does.

I appreciate that you are feeling all introspective, but that skull BELONGS TO SOMEONE.

Girl, no. You need to dump him yesterday.

Look, kid, that haircut? It does not scream “KING” to me. It just doesn’t.

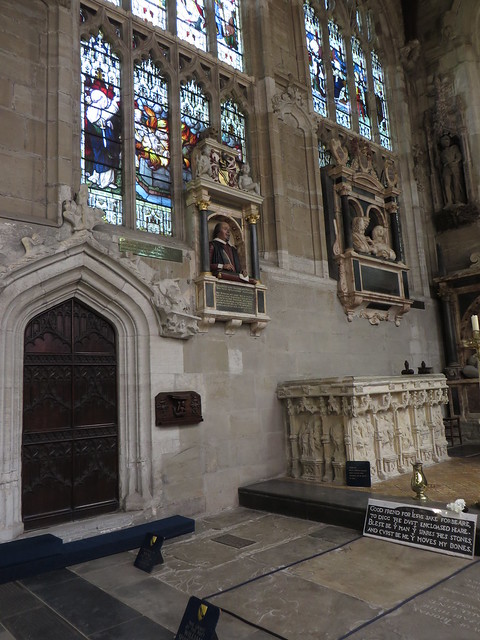

At a quiet end of town in the Church of the Holy Trinity was the man himself, interred beneath the stone tiles. I had no idea. I’d always thought he was in Westminster Abbey, if anywhere. But the real issue I grappled with was that he was mortal; he lived and died on this earth.

It seemed an impossibility; he is a rhapsodist that age can not wither, that custom can not stale. And yet his grave lies beneath the stones in the same church where he was Baptized.

Admission is £3.

Note that you can visit Holy Trinity without paying this fee, but the grave is partitioned off in a corner, accessible only to ticket holders.

I readily paid admission in order to get a better look, to read the words on his grave.

Good friend for Jesus sake forbeare,

To dig the dust enclosed here.

Blessed be the man that spares these stones,

And cursed be he that moves my bones.

Supposedly Shakespeare wrote those words himself. Which makes sense, because if you’re literally Shakespeare, can you really leave your epitaph to someone else?

My beloved, paying his respects to the great minstrel.

Oh, and my brother and sister-in-law drove down just to see us. Let us appreciate how adorable they are for a brief moment:

Note how much taller than me my brother is. Also, MY PANTS ARE BASICALLY FUNFETTI.

And you remember why you travel. To make the world less small, to move closer to those who are far away.

We wandered to his birthplace after that – far more expensive than the church, though admission is good for a year, should you wish to become a repeat offender in this pilgrimage of dorkery. The house sits in the middle of town.

The papers adorning the front are assignments from schoolchildren.

This is the window that hung in Shakespeare’s birthroom. The window panes are etched with the names of visitors over the years.

This is the room where he was most likely born.

Pardon the abysmal composition of this photo of Shakespeare’s birthroom. Let us say that I was overcome with the history of the place. Let that be my excuse.

This small corner of the floor was preserved to look as it did when Shakespeare was a child. He likely toddled over these stones at some point, and now I walked on them.

Shakespeare as a toddler. Can you even imagine?

From an upper window a woman in full costume called down to a man in the garden below, and the two of them recited lines from the balcony scene of Romeo and Juliet and my heart burst from my chest and did cartwheels around the room.

Later, we would see them again in the garden below, delivering lines from his other works (UPON REQUEST!), including the sharp back and forth of Beatrice and Benedick in Much Ado.

I remember thinking, “They have the greatest job in the world.” And for reasons I can’t quite explain, I wanted to cry.

An expansive Shakespearean museum is seamlessly attached to the cottage, so you move from his childhood home into galleries that hold artifacts from his life.

In the center of Stratford, there had once stood a large cross where merchants – including Shakespeare’s father, a glovemaker – would sell food and goods on market days. This is the stone base atop which the Market Cross once stood.

William Shakespeare was so moved by this old lumpy rock that he wrote an entire play about it. It was called King Lear. (I KID. It was called Richard III.)

The placard next to it noted that it was one of the few objects in the museum that Shakespeare would have interacted with and touched in his lifetime. And, as silly as it sounds, the significance of this worn rock did not escape me.

I was in Shakespeare’s hometown, looking at relics from his world.

Not far from the base of the cross is a copy of The First Folio, one of the most valuable books in existence.

It was the first collected edition of Shakespeare’s work, published in 1623. Without it, we would have lost more than half of Shakespeare’s plays. It is believed that somewhere between 750 – 1000 copies of the First Folio were originally printed, but because the printing was was done by hand, no two were exactly alike. It’s believed that around 230 copies of the book have survived.

It’s like a touchstone for the Western World.

A short walk from Shakespeare’s birthplace, near the banks of the Avon river, is the Royal Shakespeare Theater. If you take the elevator up to the tower you can look out over Stratford from a vantage point that Shakespeare would have never known.

Looking out, the utter smallness of it hit me. Stratford is tiny. But the works of its most famous son reach out across the world.

They are everywhere.

They are studied by students young and old …

They are imbued into nearly every facet of modern culture …

And they are an irrevocable part of who we are.

Leave a Comment