I’m An American Traveler. Here’s Why I Won’t Pretend I’m Canadian.

The refrain I’ve heard again and again among American travelers over the last six months has been this: “Time to pretend we’re Canadian.”

That seems to be the best way to avoid having to explain, well, anything that’s going on in our country. We can gently maneuver around any awkward conversations about the demise of democracy and we can get out of answering that ever-present question, “What the fuck is going on over there?”

And I get it. I, too, have been tempted to pretend I’m from the Great White North, with its socialized healthcare and Prime Minister who looks like a long lost brother to Luke and Owen Wilson. I’ve seen countless episodes of DeGrassi. I can tell stories about when I was in “Grade 3”. I can systematically change my pronunciation of the diphthong /au/. PUT ME IN COACH, I’M READY TO PLAY HOCKEY OR WHATEVER!

This would be a simple and easy thing to do. But there are a couple of problems. I am from Seattle, or, as Canadians would call it, “the tropics”. We get 308 cloudy days a year. Canadians will look at my sun toasted skin, from those 57 almost-sunny days and know that something is amiss. And I’m not nearly polite enough to be Canadian. The other day I bumped into a mannequin and failed to apologize. A true Canadian would have. They apologize to everyone and everything. They apologize for the weather. It’s the national pastime, after curling.

But the main reason I absolutely won’t tell people I’m Canadian is this: I am American. And now, more than ever, I need people to know that fact.

My identity as an American is one I’ve fought for. My family history does not stretch back to sepia colored photos at Ellis Island. We haven’t been in the new world for so long that I needed to search a family tree to find out my history. I knew exactly what it was. My family came to the U.S. in the late 70s, bell-bottomed and big-haired. Because of this, I’ve been told time and again by people from all over the world that this country does not belong to me, nor I to it. That my European roots, and placement in the first generation of my family to be born in here somehow exempted me. But these things don’t conflict with my identity as an American. They simply confirm it. My family is made up of immigrants. My mother first waddled over here, heavily pregnant with me. My father first set foot on this country when he was a kid, fresh off the boat after spending time in a displaced persons camp in Germany. My friends have similar stories. They are the descendants of immigrants and slaves, they are the descendants of people who were displaced or slaughtered or overthrown. Our origin story is complicated and diverse and ugly. That is what it means to be American.

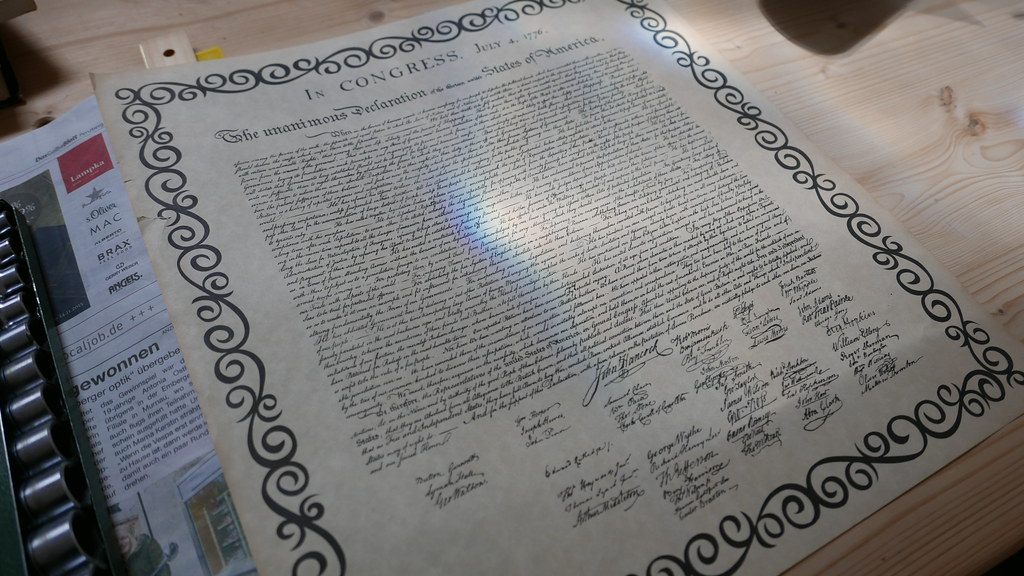

I found a copy of the Declaration of Independence in my dad’s workshop after he died. He lived in Germany for most of his life, and was born in Russia. But he was adamant: he was American.

I had a friend whose national identity came and went with the political tides. When our country shined, she did as well. She delighted in Obama’s election, high-fiving people as though she’d single-handedly made it happen. But whenever things turned dark, her language would switch from “we” to “you”. “You Americans did this.” or “Your country did that.” She was quick to disown it. It wasn’t her problem, and it wasn’t her country to fix.

This always bothered me, and yet I almost envied her for the freedom it offered. Her love for our home was conditional. Mine isn’t.

America has more than its share of problems. Our police brutality. Our systemic oppression and murder of young black men and women. We treat poverty as though it is a crime. We tell people that healthcare is not a right, and we make it so prohibitively expensive that only the wealthiest can afford it. We do not require maternity leave. We have eradicated Native American history. We’ve eradicated Native Americans. We are the only country in the world that still disputes climate change. We really need better access to birth control and sex education. College is too expensive. Schools are underfunded. Speaking more than one language should not be considered snobbish, but somehow, it is. The Supreme Court is still way too much of a sausage fest. We vilify Muslims on a daily basis. Our gun violence is staggering. I can go on. I can fill post after post.

These are America’s problems. And the second I separate myself from being an American is the second I abdicate responsibility. I’ve given myself an out. I don’t have to worry about it. I can critique without doing anything to make the situation better. I can judge the system without having to acknowledge how I benefit from it. It’s happening in someone else’s country, not mine.

If everyone who sees America’s problems claims to not be American, who is left to fix things?

Seen at the Women’s March in NYC on January 21, 2017.

Last fall, when a tour guide in Turkey found out where we were from, he shook my husband’s hand.

“We haven’t seen Americans lately,” he said. And I realized the weight and responsibility we carried along with our passports. We were ambassadors for our home.

Now seems like a terrible time, politically, to tell people where I’m from. That’s precisely why I’m doing it. As I travel internationally, headlines from around the world announce the U.S.’s Muslim ban, the repealing of environmental regulations, the rise of anti-Semitic groups. I need to defy all of that as an American. I need the people I meet to know that the policies and actions of my government do not reflect the opinions of all Americans. They don’t even reflect the opinions of most Americans.

At a time when so many people in America living in fear of deportation because they aren’t citizens, it feels particularly wrong to pretend that I’m not one. At a time when people keep their ethnicity a secret out of fear of being targeted, I need to realize the privilege that comes from being a white woman with an eagle on her passport. There are people who were born here, whose families have been here for generations, who have never truly felt that this was their country. They’ve spent generations believing that the American dream didn’t apply to them because it didn’t. I have an obligation to work to make them feel as though this country is theirs, too. And I can’t do any of that if they think I’m from Vancouver.

I don’t deny Canada is a grand place. It gave us both Ryan Gosling and Ryan Reynolds. It gave us Drake and The Weeknd and … Keanu Reeves? Keanu is CANADIAN? (Dear god, all our best celebrities are from our neighbor to the north.) But Canada and its heartthrob Prime Minister don’t need good PR right now. And so there is no maple leaf on my backpack.

I will travel. People will ask where I’m from. And I will answer: I’m an American.

What’s that, you say? I don’t seem like an American? Sit down, friend. Let me tell you why you’re wrong.

For the people who inevitably ask: what if you are traveling somewhere that isn’t safe for Americans? Dudes, I go to central Europe most of the time. If you are in a place where you don’t feel safe, you need to do what makes you comfortable, and no one gets to judge you for that.