Going Against Nature: Sick in NYC

View out our porthole window, the Maritime Hotel.

–

Do you ever have those moments where you pull something off (a meal, an event, a project), and it comes together so beautifully, and was almost effortless, that you are tempted to think, “This is my calling. This is what I was put on this earth to do”?

I totally haven’t, unless you count cake eating, which I’ve been repeatedly told is not a calling.

Usually I have quite the opposite feeling: I’ll try something, and it will be such an epic disaster that I am able to say definitively that genetics and the universe clearly never intended for me to carry out these tasks.

Were I to write them all down, I’m fairly certain I could fill volumes. Here is an abbreviated list of things that I will never master:

- the baking of custard-filled pies

- The Electric Slide

- recognizing that the GPS is inanimate, and not trying to mess with me

- small talk

- liquid eyeliner

As of late, I’ve been tempted to add one more thing to that list: travel.

Because as much as I do it, there are moments when it becomes clear to me that I was absolutely, under no circumstances, meant to. Given my stature, this is clear: I am endowed with a shape that can best be described as “ripe pear” (heavier on the bottom, squishy at parts, and TOTALLY FRIGGIN DELICIOUS, I might add). I’m clearly designed to be pulling a plow across a field somewhere in eastern Europe, and every now and then and I’d squat and unleash a child or two from my loins, swaddle them up, and go right back to tilling the soil or whatever.

This, obviously, was my calling in life, and I was just born in the wrong decade and hemisphere.

I was, under no circumstances, ever meant to travel. On our last trip to New York, the universe decided I needed a reminder of this fact.

We’d just landed in Newark after a slightly (but not unusually) turbulent flight from Seattle. My stomach felt queasy, despite the consumption of a half bag of ginger candies.

Rand was trying to think of the smoothest, fastest way into the city so as not to exacerbate my motion sickness. He suggested the subway, but I shook my head. I reasoned that a cab would be fastest, and if I needed to throw up, I could do so on the city streets, and not in the middle of the A train.

And so we ended up in a yellow cab, zipping onto the Jersey Turnpike, and then barreling down the Holland Tunnel, until we finally were swerving, sliding, and occasionally jerking to stops on the streets of Manhattan. I leaned my head back against seats that smelled like old coffee, exhaust, and cigarettes, and tried to look at the horizon.

The problem is that, from most parts of New York City, you can’t see the horizon.

I breathed in through my nose sharply, slowly releasing the air through my mouth. You will be fine, I told myself. You will not throw up. Soon you will be at the hotel, and you will lie on the bed, and the sheets will be crisp and cool and you will feel better.

Soon.

And sure enough, after an excruciating ride we were at the hotel, and the bed did have sheets that were crisp and cool. But I was unable to keep my part of the deal.

An hour later, I was slumped on the floor of the bathroom, the seat of the toilet cool against my cheek. I had emptied the contents of my stomach in the bowl twice so far. There was nothing left inside of me, but my body, in a vain attempt to rid itself of the poison that must have caused this, continued to lurch, violently, into dry heaves. The spasms clenched my abs until they hurt.

“Kill me now,” I whispered up to Rand, who stood in the doorway, nonchalantly.

“Oh, please,” was his reply to my melodrama. “You’ve been way worse.”

It’s not that he was unsympathetic. It’s just that this was very, very true.

He’d seen me in this state before, or worse, many times.

“It’s normal,” he said, in an attempt to comfort me. I am pleased to say that despite having a pallor the same color as the walls of a state penitentiary, I was able to give him a look of pure incredulity.

“It’s probably just food poisoning,” he said, refusing to admit that there was something fundamental about me that was prone to sickness. Something inherent in my being that leaves me unfit for travel, but totally fit for growing kohlrabi in eastern Siberia.

I shook my head. Rand had eaten nearly identical meals as I had that day. And it seemed odd that my food poisoning would coincide perfectly with a turbulent flight followed by a twisting cab ride into Manhattan.

No: this was the universe trying to tell me something. Mainly, that I was not born to be a traveler. As though my pitiful sense of direction wasn’t enough to clue me in on that.

I lay on the floor of the bathroom, soothed by the smell of bleach on the freshly laundered towel underneath me, and marveling at how pristine the toilet bowl was, even from this angle. My compliments to the housekeeping staff at the Maritime Hotel in Chelsea, who did a bang up job, and my apologies for fouling their immaculate work with my lunch.

I did not make it to the dinner that we had planned with friends that night. I tried. I really did. I even managed to put on some clothes and deodorant, and spent roughly 15 minutes with them in the hotel bar (with a brief interlude to the bathroom downstairs to throw up again) before realizing that perhaps I wasn’t going to be the best dinner date.

I shooed them off, delighted that I could be a selfless martyr.

“Go on without me,” I said, mercifully not subjecting them to goodbye hugs that would have likely smelled like barf.

Back in the room, I turned on the A/C as high as it went, lay on the bed without a blanket over me, my jeans in a rumpled pile on the floor. I hoped the cool air would kill whatever was inside of me.

I dozed, noting on the edge of my consciousness how the light in the porthole window was fading to deep blue and orange – the last few sunsets of the summer in Manhattan.

I awoke a while later, the sky outside now dark, the sounds of traffic below drifting up and into the room. The city outside didn’t care if I was sick. It was moving and bustling. Outside, life was happening. Tomorrow, I told myself, I would be a part of it. And just knowing it was there, just knowing that I wasn’t alone – not really, because how could you be in the city? – made me feel better.

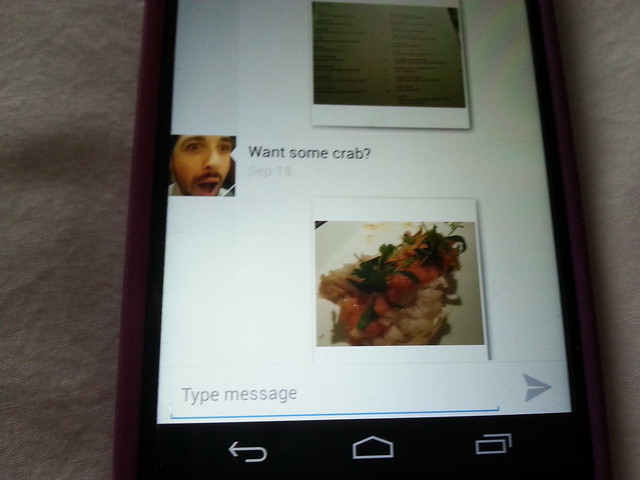

I checked my phone. Rand texted me from the sushi restaurant where they were having dinner.

“Do you want me to bring you back something?” his message read. “How about some crab?”

And then, god help me, he texted me a photo of the crab roll they’d ordered.

–

I managed to laugh at gag at the same time – a first for me. He didn’t mean to traumatize me – he just had no idea how to soothe a churning stomach. Hell, this is a man who can read in the car. He doesn’t even know what it’s like to be motion sick.

“No, no!” I texted back, laughing so much that my overworked abs ached. “Saltines,” I wrote. “And Gatorade.” He returned with both (“I got you blue Gatorade, because blue is the best flavor.”)

I laid on the bed and listened to the story of his night, running to throw up two more times in between. I tried to get him to explain his logic in offering to bring me back sushi; he was unable to. I couldn’t help but smile.

Perhaps he wasn’t meant to have a sick wife. And perhaps I wasn’t meant to to travel. But sometimes the universe’s plan for you – the things that would come easily – aren’t what you want. And so, even though you are calm and not prone to illness, you marry the pukey, ill-tempered girl. Or you decide to spend all your free time traveling, when just the act of bending over to tie your shoes makes you queasy.

And at the end of the day, you lay down on cool, crisp sheets, and find you are perfectly okay with that decision.

Leave a Comment